Eddie Izzard takes on Lenny Bruce's mantle. But can we still be shocked?

Susannah Clapp

HE BECAME FAMOUS as the comedian who talked dirty and died of an overdose. His idiom was characterised by Kenneth Tynan as 'jazz-Jewish'. He is remembered by George Melly as looking something like a modern rabbi and something like a lemur. His ferocious, free-wheeling riffs paved the way for alternative comedy.

When Lenny Bruce came to England from America in 1962, he divided the theatre-going London. Enthusiasts such as Melly and Tynan loved the sort of joke that described a Madison Avenue plot to boost cigarette sales by making cancer a status symbol: 'I was in Nassau last week, and everyone had it.' They liked the stories that clustered around Bruce when he wasn't on the stage: he was said to have hired a team of prostitutes and trained them to sing, in three part harmony in his hotel 'Please love me, Lenny.' They thought he had new things to say about a society which found watching pornography more shocking than watching war films. They found him in person, according to Melly, 'curiously lovable and vulnerable'. And they often found him flying on drugs. Taken to the Mellys' Hampstead home after a gig, he was at first convinced that he had been spirited away to the depths of the countryside. Later he decided he must be in a nightclub, and couldn't understand why, when Melly performed his 'Man, Woman and Bulldog routine (which features lots of bare bum) while on the domestic hearth, he wasn't greeted with howls of horror from an audience. Melly gave him a crucifix made out of World War One bullets in return Bruce presented him with a cheap travelling clock.

Others walked out of his act. The actress Siobhan McKenna left Peter Cook's Establishment club after hearing Bruce on the subject of the Roman Catholic Church. A.J. Ayer also made an early exit, pronouncing Bruce 'boring'. When Cook applied to bring him back to London the following year, the Home Secretary refused him entry to the country as an undesirable alien. Posters went up in Hampstead windows pointing out that the Home Secretary was a fool and Bruce was a genius.

Two kinds of danger were involved in what Bruce did on stage. He said things which caused individuals and institutions to storm: he was constantly being arrested for obscenity. And he went without the safety-net o f a rehearsed script; he improvised, he rapped, he took off and he sometimes fell down. He wasn't consistent. Quite often he wasn't funny.

It's probably impossible to recapture the outrage and the exhilaration that he provoked. There is scarcely the shadow of a shock in Julian Barry's Lenny, a creaking vehicle for Bruce's turns at the Queen's Theatre. No one is going to be alarmed by the inclusion of the word 'cocksucker' in a satirical piece- indeed, its use might be considered mandatory. But Bruce was arrested for using it. Barry's play, framed by a fantasy courtroom sequence, gives brief biopic glimpses of a showbiz mother, a marriage to a stripper, the narcotics, the arrests, the illnesses. It does so without providing any insight into - indeed,hardly any sight of the society which made Bruce snarl. Peter Hall's production makes every creak a groan. William Dudley's design - a mirrored wall, a flat pink picture of New York skyscraping - is Fifties coffee bar exotica. In front of it, jazz musicians lounge around on the floor, clicking their fingers and addressing everyone as 'man'. The whole thing screams cool: but cool never screams.

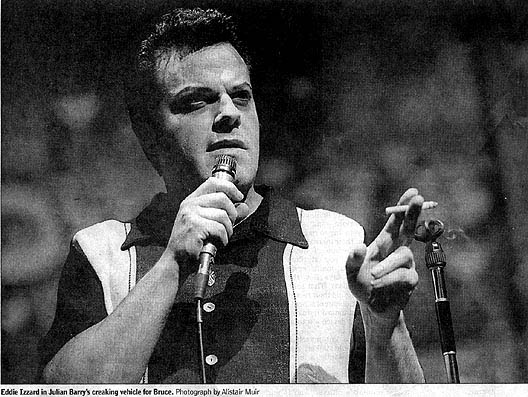

And yet, in the middle of all this, Eddie Izzard is often captivating as Bruce. Frequently naked, with his hair sleeked black and back into a quiff, he is nonchalant with the best jokes - Why did the Mafia want to kill Einstein? Because he knew too much. He performs Bruce's dialogue with a drum - in which drum-beats echo the rhythm of a sex chant - with an inquisitive excitement that suggests his words are being conjured up on the spot. When he invites the audience to take the curse off discrimatory words by joining him in a chorus of 'Good morning Mr Nigger, how are you today?' he manages to raise an uneasy mumble from the auditorium.

But he isn't actually anything like Lenny Bruce. What he offers is not an impersonation: it is quite different from the detailed evocation of another delightfully scabrous presence provided by Peter O'Toole in 'Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell'. Words and personality are at odds here. Izzard may flaunt and float on a sort of naughtiness, but his gift is to charm, to get the audience on his side. Lenny Bruce went in and carved them up.